My analysis of a beautiful and mesmerizing keyboard piece by François Couperin -- a piece I have arranged for TTBB and SATB

a cappella (both arrs. available on this site)

Couperin's "Mysterious Barricades"

François Couperin frequently supplied his harpsichord pieces with fanciful and descriptive titles, such as La Voluptueuse, La Prude, Les idées heureuses, and Les langueurs tendres. In the preface to his first volume of harpsichord suites or ordres, Couperin wrote: "I have always had an object in writing each of these pieces, furnished by various occasions. So the titles correspond to ideas which have occurred to me." And he added, "I shall be forgiven for not going into greater detail." Apparently, like later French composers—Satie with his impenetrable titles, and Debussy coyly placing the descriptive names of his Preludes at the end of each piece—Couperin felt that a little vagueness would give listeners’ imaginations greater scope.

With a few of his titles, and particularly Les baricades mistérieuses, from his sixth ordre, Couperin "seems to enter the world of metaphor," as the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians says, "where meanings are no longer unambiguous"—leaving us to ponder what his "object" could have been in writing this piece. and what possible relation the piece could have to the idea of defences or obstructions.

One possible explanation is in the dense texture of the piece. Its low range and interwoven rhythms do present an aural and visual image of obstruction, or at least of a tightly-knit fabric. The piece is technically in the style luthée or style brisée, a "broken" style derived from lute-playing, in which chords unfold diagonally rather than being sounded vertically: the upper notes are displaced in relation to the bass-line and each other, and these displacements are so arranged as to create a composite rhythm of continuous eighth-notes. There is no melody as such, but rather four distinct strands, which Couperin treats for the most part as proper contrapuntal voices.

If we pull apart these strands, we find a rhythmic heirarchy in play. First, a bass-line moving almost exclusively in steady half-notes. Just above that, and syncopating against it in a consistent pattern, is the tenor voice. Paired with the tenor is the soprano, which also emphasizes offbeat quarter-notes, occasionally adding eighth-note upbeats or other decorations. The most rhythmically complex voice is the alto, which fills in the eighth-note gaps by syncopating against the the tenor and soprano. The alto line almost never articulates a note on a beat or even a half-beat, but constantly lags a quarter-beat behind the harmony—while seeming to edge ahead rhythmically, by virtue of its nervous energy.

This diagonal relationship of the upper voices to the bass creates some extraordinary dissonances in passing, such as the jazzy A-flat M7 9 chord on the downbeat of bar 52, or the crunchy E-flat M7 at bar 71. On the harpsichord, and to some extent even on the piano, because of the decay inherent in their tone, these dissonances could be passed over without much notice; but a little rubato, combined with sensitive articulation (on the harpsichord) and voicing (on the piano) can bring out their expressive potential.

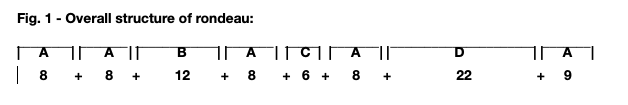

These fleeting moments aside, the harmony of the piece as a whole is simple; but harmonic considerations play a large part in the overall structure and character of the piece. Structurally, the piece declares itself in the published score to be a rondeau, a form in which a recurring refrain (which we will call the A section) alternates with contrasting sections (which Couperin actually labels in the score as première couplet, deuxième couplet, and troisième couplet, and which in the analysis below we will call B, C, and D). As Fig. 1 shows, there is a pleasing asymmetry among these sections: B lasts 12 bars, while C is a brief six, and D an expansive 22, bars long.

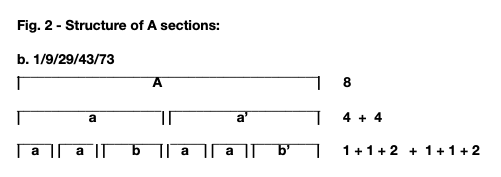

This is in contrast to the symmetry that prevails within most of the sections. For example, the eight bars of A can be broken down as in Fig. 2.

Each of the one-bar-long a’s is a progression from tonic to dominant, and the numerous repetitions of that progression give the section a sense of constantly turning back on itself. The two bars marked b’ cadence on the tonic, bringing the section full circle, as it were.

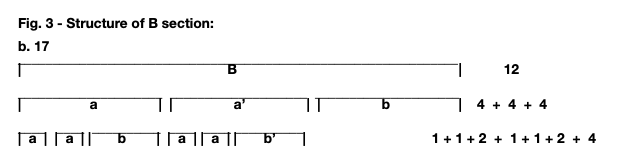

The B section centres around the dominant (V), F Major, and has a slightly more elaborate symmetry (see Fig. 3).

In the first four bars of B, two iterations of the I-V progression are followed by a descending bass-line moving to the dominant. The next four bars mirror that with two iterations of the progression V-II followed by a rising bass moving back to the dominant. The last four bars are a transition, preparing for the return of A.

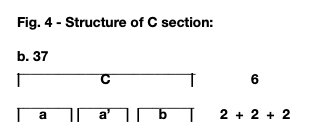

Section C centres around the supertonic (ii), C minor, and breaks down as follows:

C is unique in giving special prominence to the soprano line. So far restricted mostly to repeating pedal-points, with the occasional ornament or fragment of melodic motion, here the soprano "sings" a five-note descending scale, then sequences that up a fourth, reaching its highest note thus far; then at bar 42 the soprano takes over the texture entirely—to the extent that the tenor part is reduced to merely doubling the bass in octaves before joining the alto in dropping out altogether until the return of A. This is the one moment in the piece where Couperin abandons his model, strictly observed everywhere else, of treating the four parts as individual contrapuntal lines.

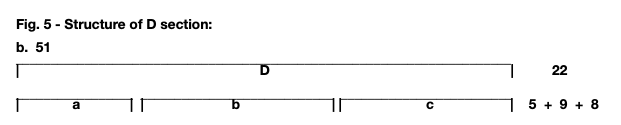

The expansive D section is notable for the irregularity of its phrase-lengths. It begins with five bars directed toward the subdominant (IV), E-flat, then takes a wide-ranging nine-measure tour of the circle of fifths, arriving (in bar 65) back at the tonic, where it hovers for eight bars before the final appearance of A (see Fig. 5).

The use of the circle of fifths seems to have special significance in the context of the other manifestations of circularity in this rondeau. It certainly takes us "the long way" from E-flat to B-flat—via A, D, G, C, and F!

Bars 65-73, which I described above as hovering around the tonic, are eight of the most minimalistic—and, I think, most beautiful—bars in all Baroque music. Each voice subsides into a murmured mantra of its own—the bass repeatedly approaching the fifth of the chord, F, or its upper neighbour, G, from the D below; the alto constantly circling that F an octave higher; the soprano absorbed in its B-flat; and the tenor gorgeously toying with the third of the chord and its lower neighbour before finally, reluctantly, signalling the end of the trance by inserting the upper neighbour, E-flat, which sighs itself into satisfaction as the refrain returns.

At the final bar, a ninth bar added to the final refrain, all the voices at last settle together onto a downbeat. It is worth observing that the very first bar of the piece lacks a downbeat: Couperin chose to begin not with a bass-note, but with a rest in all parts, and the first note we hear is actually the alto voice syncopating against silence! It is as if we have joined the piece in progress; and now at the end we realize that the final cadence is almost arbitrarily imposed: the last downbeat could just as easily launch another repetition of A, or of the entire piece; or it could be the beginning of a hypothetical extension of the rondeau out into eternity.

Perhaps there is a hint here as to the true meaning of Couperin’s title. "Les baricades mistérieuses" places us in a labyrinth, similar to the intricate hedges popular in royal and noble gardens at the time it was written. As we listen to or play the piece, we follow various paths through its musical maze, some shorter and some longer, only to return to where we began. We can experience the many repetitions, turnings, and circlings as impediments to progress, and be constantly frustrated by the returns to square one; or we can immerse ourselves in the experience of departing and returning, and allow ourselves to forget time and linearity. If we do the latter, the barricades mysteriously disappear.

Copyright © 1999 Stephen Smith